How Can i Be Without Border

Mckenna Goade • December 15, 2024

Composting Communications

December 15, 2024

Composting Communications: How Can i Be Without Border?

The corpse (or cadaver: cadere, to fall), that which has irremediably

come a cropper, is cesspool, and death; it upsets even

more violently the one who confronts it as fragile and fallacious

chance. A wound with blood and pus, or the sickly, acrid smell

of sweat, of decay, does not signify death. In the presence of

signified death—a flat encephalograph, for instance—I would

understand, react, or accept. No, as in true theater, without

makeup or masks, refuse and corpses show me what I permanently

thrust aside in order to live. These body fluids, this

defilement, this shit are what life withstands, hardly and with

difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of

my condition as a living being. My body extricates itself, as

being alive, from that border. Such wastes drop so that I might

live, until, from loss to loss, nothing remains in me and my

entire body falls beyond the limit—cadere, cadaver.

- Julia Kristeva, Approaching Abjection

…

“He had stage 4 colon cancer for 7 years.”

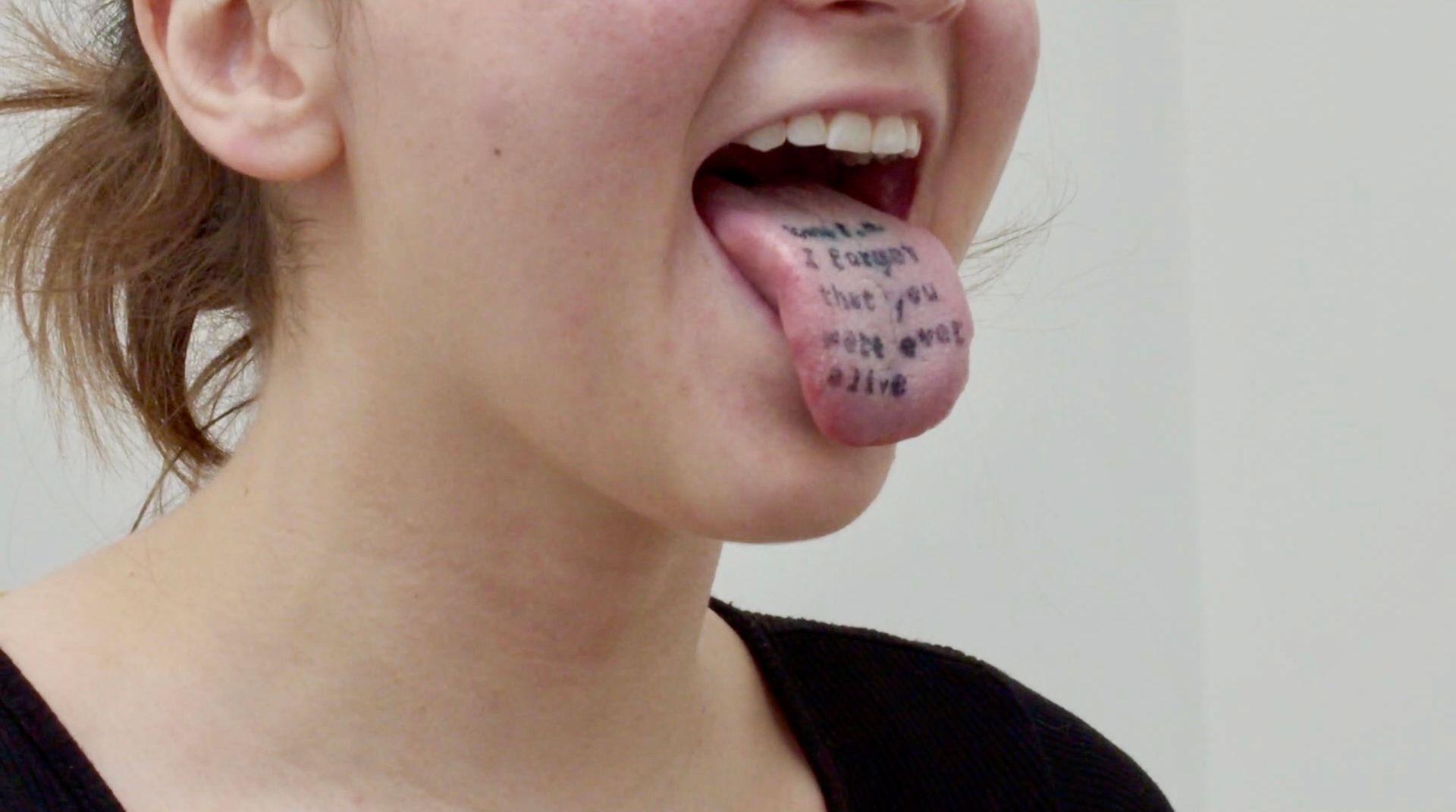

These words taste bad on my tongue, but my lips love to say them.

“He had stage 4 colon cancer for 7 years.”

As if to explain his prolonged deterioration.

“He had stage 4 colon cancer for 7 years.”

As if it made it any better or worse.

…

“My dad died from stage 4 colon cancer.”

I’ve said it so often the words no longer have meaning.

“My dad died from stage 4 colon cancer.”

Is this really the easiest way to say it?

“My dad died from stage 4 colon cancer.”

—— I don’t think I ever realized it was a lie.

I don’t mean to say that cancer didn’t play a role in his death,

Because cancer did fill his lungs with fluid.

He couldn’t breathe.

He suffocated.

He drowned…

I used to make paintings about death, cyclical time, the body, barriers/edges/corners… but the work did not engage in these cycles I was so obsessed with. The materials of oil paint on canvas were created to be long-lasting, to trick artists into thinking they could hide from oblivion by creating something “archival.” I, too, fell into this trap as I considered the little physical legacy my father left behind. At one point, I considered attempting to make things that never died—an impossible quest to make immortal work that would ensure my place on this earth forever. But how long can you hold onto immortality when deterioration surrounds us? We are always dying, and we are always being born.

My grasp on making archival works quickly loosened as I felt the urge to embrace something else. Instead of running from inevitable entropy, I look to the moment when the ‘self’ deteriorates to the ‘other’ as the very place where we find meaning—the place where “I behold the breaking down of a world that has erased its borders: fainting away.”

I’m preoccupied with edges.

When I see a painting on a canvas

I tilt my head and shift to the side.

I press my face against the wall

Just to catch a glimpse of how they folded the corners.

Did they tape the edges to leave the raw canvas showing? (sexy)

D rings and a wire? French Cleats? A nail?

If we painted the land of the living, where would its edges be?

For reasons unknown to me, the moments where a painting meets the wall have always been the most important part of the composition. Maybe this significance was derived from my pursuit of finding where the edges of my material world meet the contours of the land of the dead. I ask, per Julia Kristeva, “How can I be without border?” These distances build my desire—can there be desire where there are no edges?

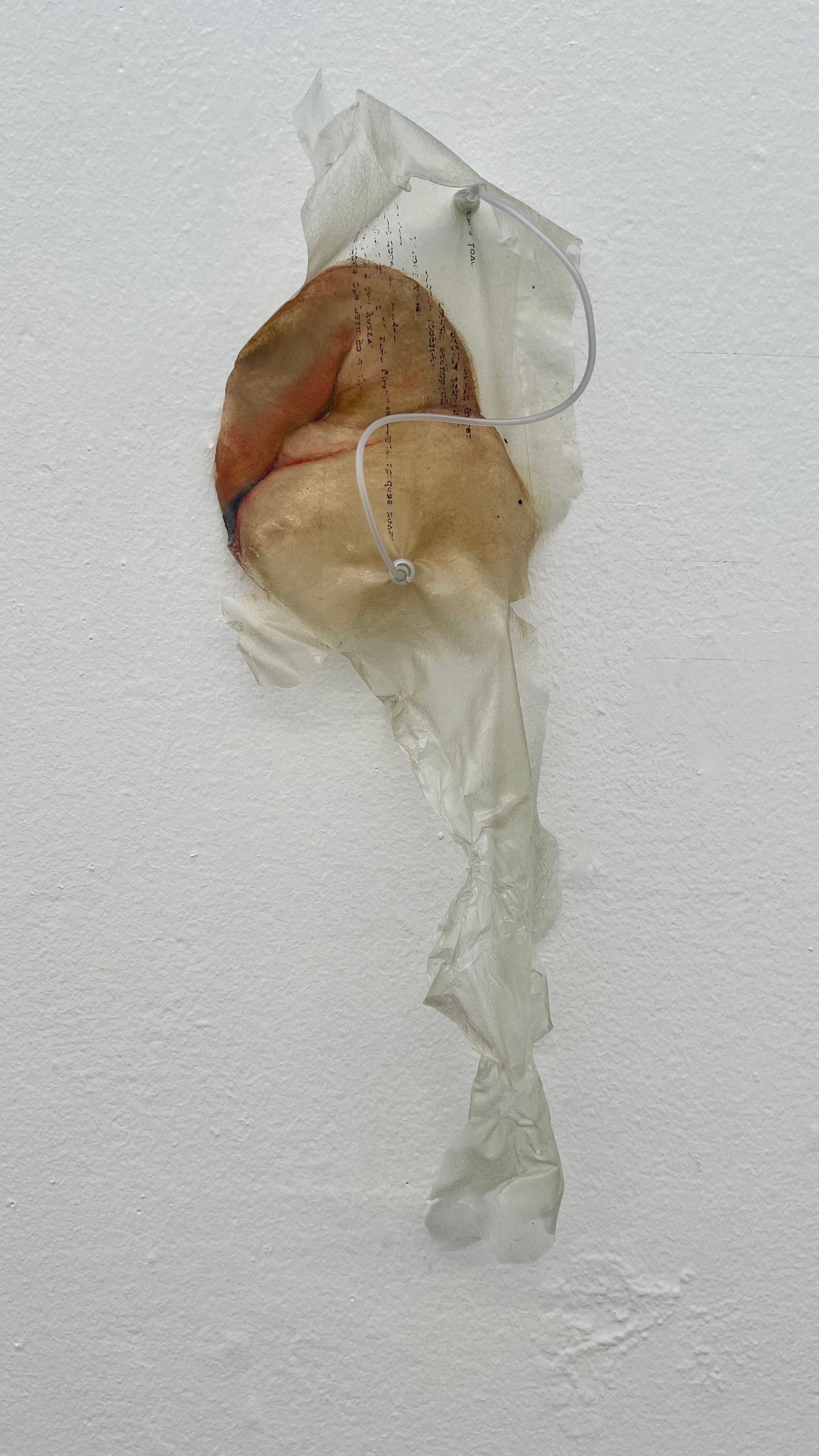

When considering borders, edges, barriers, boundaries, contours, outlines, and partitions, I first think of my skin. My skin is the surface where I meet the world. It is a boundary—but one that breathes. My skin touches air, and it touches my insides. My skin touches, my skin folds, my skin stretches, my skin sags, and my skin will wither… My skin's porous, changing surfaces cannot be preserved. I communicate through this barrier every day. Despite its disguise as a separator, it is the surface where I can connect with all that surrounds me. As Stacy Alaimo claims, “‘Nature’ is always as close as one’s own skin.”

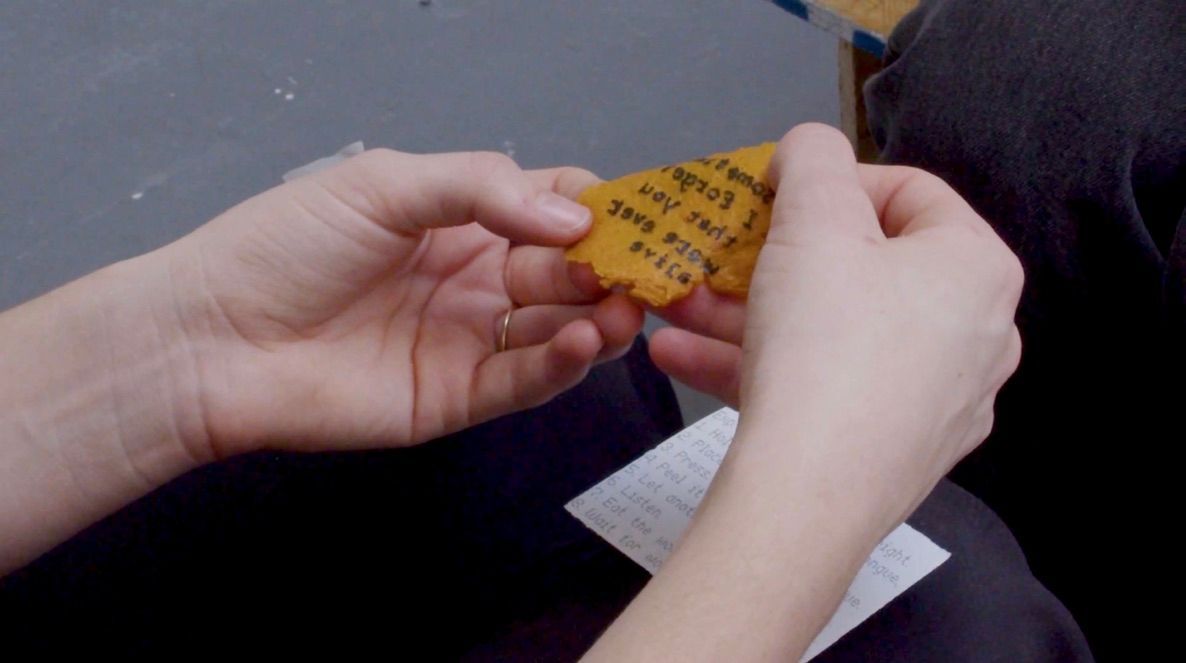

Our Earth also breathes; our Earth also has skin. What messages is she communicating through her topsoil? Her algae scum? Algae is where the air touches the Earth, where Breath brushes against decay. From algae, I distill agar… and I cast bioplastic. Bioplastic is a fragile skin—impermanent, porous, always breaking down—bioplastic is slippery.

The viscous is a state half-way between solid and liquid. It is like a cross-section in a process of change. It is unstable, but it does not flow. It is soft, yielding and compressible. There is no gliding on its surface. Its stickiness is a trap, it clings like a leech; it attacks the boundary between myself and it.

When I accepted that I am viscous and that the boundaries between the immaterial and material worlds are slippery, I wanted to experience deterioration daily.

My voice (and, by extension, my breath) is a place where barriers are crossed. This breath transforms the written word into breathing letters. In Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson posits, “Letters make the absent present, and in an exclusive way, as if they were a private code from writer to reader…the act of communication [is] an intimate collusion between writer and reader. They compose a meaning between them by matching two halves of a text. It is a meaning not accessible to others.” If one’s goal is to pierce holes through varied and “separate” ecologies, should one be writing letters? Should they provide their half of the text and wait for the reader to provide the other? If Nature is, as Alaimo claims “a world of fleshy beings, with their own needs, claims, and actions” then why not try to, as Robin Kimmerer suggests in Braiding Sweetgrass, “Ask, and listen for the answer?”

I have long pursued reaching across barriers and creating ecology by touching things I perceived as out of reach. But now I am curious if one can actually touch anything. As Karen Barad points out in On Touching—The Inhuman That Therefore I Am, “a common explanation for the physics of touching is that one thing it does not involve is . . . well, touching.” Barad then explains that to a physicist, touch is the electromagnetic repulsion of your skin’s electrons against the electrons of the “other.” Perhaps the inability to contact anything builds Anne Carson’s Eros: “The boundary of flesh and self between you and me. And it is only, suddenly, at the moment when I would dissolve that boundary, I realize I never can.” Can this boundary not be dissolved because one cannot eliminate electrons? Is desire just electrons? Essentially, Barad asks,

Whom and what do we touch when we touch electrons? Or, rather, in decentering and deconstructing the “us” in the very act of touching (touching as intra-action), we might put the question this way: When electrons meet each other “halfway,” when they intra-act with one another, when they touch one another, whom or what do they touch?

In the process of decentering the “us” and communicating with the “we,” I am curious about who/what I have been reaching toward. Am I just reaching toward my “self”?

Thinking about our triangle

You, me, and the distance between.

Separation as a film

a skin

a barrier.

Is this why I want to pierce it?

I’m pressing into this plastic with every ounce of me.

But how much of me is just myself?

Or is it what once was you, and part of you

pushing from both sides?

The more I think about these barriers, the more I think they do not exist. (And maybe the only thing that distances us is translation). The “edges” of immaterial and material worlds may be represented by the implied boundaries between human/nature—but what about when these distinctions dissolve? When we imagine the interaction between human existence and the more-than-human environment through Stacy Alaimo’s “trans-corporeal” lens (trans indicating movement through), it becomes difficult to structure worlds as self/other, human/nature; instead, perhaps we are Eve Sedgwick’s “permeable we” (or Haraway’s Cyborg).

The portal to the space between

Life and Death

Inside and Outside

Self and Other

Will I find it in decomposition?

In Composting Feminisms and Environmental Humanities, Hamilton and Neimanis put forward the words of Anishnaabe and Haudenosaunee scholar Vanessa Watts. She says her society “conceives that we (humans) are made from the land; our flesh is literally an extension of soil.” To communicate with “we,” do we need the messages to return to “us?” The further I delve into this inquiry, the more I contemplate that my endeavor to communicate with the deceased may constitute an act of translation. The messages I perceive as being lost are merely mistranslated, and it is conceivable that the mechanism of this translation occurs through the process of composting.

I make art for dead people.

I’m not sure if they like it or even if they have seen it yet, but I know that they are aware of my incomprehensible desire to connect with them. I have tried facing paintings away from me and toward the wall—but in the end, I think this was just a clue for living viewers to recognize they weren’t my primary audience. I tried to dissolve the works in water, but with no image or word for the dead to read, what was I sending? Additionally, what does it mean to dissolve, and what does it mean to decompose (is there a difference)? I think I have landed on composting; maybe that’s how I send letters to the dead. Perhaps this simultaneous dissolution of “self” and connection to “other” is where the immaterial and material worlds meet.

If I were to write you a letter

How would I send it?

Maybe it needs to be nothing anymore for it to meet you.

When something becomes nothing

Does it go to Nowhere?

Can I send letters to Nowhere by making them disappear?

This disappearance is a lie. Can something truly disappear, or does it just move through porous membranes into something else? Compost is less disappearing and more reappearing.

I posit that despite its very literal intentions (dead people are often buried, so putting art in the ground might be a way for them to see it), there is something more poetic about the art of composting — a reintegration of the “I” into the “we.” Accepting that all things (including the self) will deteriorate is much more meaningful to me than making our “selves” last forever.

In conclusion, I am trying to touch untouchable things (but everything is untouchable), send messages that cannot be received (or are they just being mistranslated?), and look to where “self” composts to “other” (but I am not even sure if the self/other barrier exists). But if things cannot actually touch, there must be some kind of self/other distinction. I am/we are existing in a paradox.

Now, I am researching the permeability of boundaries—between life and death, self and other, human and more-than-human. Through concepts like Stacy Alaimo's trans-corporeality, Anne Carson's Eros, and Karen Barad's intra-action, I wrestle with the idea of touch, desire, and the impossibility/possibility of dissolving the boundaries between self and other (me and you). These reflections have culminated in a turn toward composting—not as disappearance but as a process of translation, regeneration, and connection. Ultimately, composting becomes both a metaphor and a practice, embodying the continual interplay of decay and renewal, the breaking of borders, and the profound intimacy of existing within a shared and cyclical world.

Bibliography

Alaimo, Stacy. “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature.” In Material Feminisms, edited by Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman, 237–264. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Barad, Karen. “On Touching—The Inhuman That Therefore I Am (v1.1).” Preprint. In Power of Material/Politics of Materiality (English/German), edited by Susanne Witzgall and Kerstin Stakemeier, 2015. Originally published in differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies (2012).

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966.

Hamilton, Jennifer Mae, and Astrida Neimanis. "Composting Feminisms and Environmental Humanities." Environmental Humanities 10, no. 2 (November 2018): 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-7156859.

Haraway, Donna. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century." In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149–181. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Kristeva, Julia. “Approaching Abjection.” In Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, translated by Leon S. Roudiez, 1–31. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

-127. “If two faces look into each other’s eyes, can one then say that they are touching? Are they coming into contact—the one with the other? What is contact if it always intervenes between x and x? A hidden, sealed, concealed, signed, squeezed, compressed, and repressed interruption? Or the continual interruption of an interruption, the negating upheaval of the interval, the death of between?”[i] -126. I want to stay longer inside the waiting. The kind of waiting that doesn’t pretend to be meaningful. The waiting that fills hours with nothing but the sound of machines breathing for someone else. The waiting that produces no insight, only posture—how the body learns to sit without shifting, how the eyes learn where not to land. Waiting teaches the body to compress itself around possibly unrewarded anticipation. -125. Maintenance is never spectacular. Care appears to involve repeating the same action because stopping would reveal how fragile everything always-already is. -124. It feels like being asked to confirm the same information again and again: name, date of birth, emergency contact, family medical history, list of medications, circling symptoms, circling pain on the body. -123. Instead, I want this to remain slightly open. Like a seam that hasn’t been sealed yet. Like something still warm underneath. -122. I am suspicious of clarity that comes at the cost of complexity. Clarity smooths over contradictions and labels that sensation as “understanding.” But what if understanding requires staying with opacity -121. Sometimes I think the body is less a container than a threshold. Skin is not a wall but a membrane tuned to pressure, temperature, and vibration. To feel is to be crossed. To be alive is to be unable to fully seal oneself. -120. Two 20-by-20-inch squares composed of compressed compost, resting on the ground. -119. What will the multitudes of bacteria that metabolize landfills make of their ingredients—of themselves as they proliferate and differentiate into new forms, or of the geosphere and biosphere? -118. We are oozing, seeping, weeping, rotting, entangled, sniffing, compacted, leeching, filtering, oozing, seeping, weeping, rotting, entangled, sniffing, compacted, leeching, filtering. -117. If contact is only an interruption, why do I so desire it? -116. In the hospital, time presses. It gathers weight. Minutes thicken. A day does not move forward so much as deepen. The past is not behind me there; it pools beside the bed. The future does not arrive; it hovers, unformed, like a smell I can’t place. -115. I imagine the archive at night, after everyone leaves. The objects remain, still separated, still labeled, still off-gassing. Preservation continues without witnesses. The archive does not sleep; the archive slows. -114. I’m stuck thinking about a candy wrapper and how long they last compared to what they contain. -113. Sometimes I imagine language as a landfill liner—geomembrane stretched thin beneath layers of thought, designed to prevent seepage but never fully succeeding. Words buckle under the weight of what they are meant to contain. Meaning leeches. -112. The museum display case teaches how to look without touching. The landfill teaches me how touching continues without looking. These are different pedagogies of relation. -111. When I think about becoming-with, I think about the risks we don’t like to name. Becoming-with parasites. Becoming-with toxins. Becoming-with systems that don’t want us. Kinship is not a guarantee of mutual benefit. It is a condition of shared exposure. -110. Today, they figured out that the work was actually about him. I thought I had forgotten too. -109. Prepared Subgrade, Compacted Clay, Geomembrane, Leachate Water Filtration System, Filter Geotextile, Leachate Collection Layer, Waste, Daily Cover, Waste, Daily Cover, Compacted Clay, Geomembrane, Drainage Layer, Protective Cover Soil, Top Soil, Cover Vegetation. Or. Cover Vegetation, Top Soil, Protective Cover Soil, Drainage Layer, Geomembrane, Compacted Clay, Daily Cover, Waste, Daily Cover, Waste, Leachate Collection Layer, Filter Geotextile, Leachate Water Filtration System, Geomembrane, Compacted Clay, Prepared Subgrade.[vi] -108. I point toward the slow collapse of boundaries, recognizing that even in our best attempts at separation, we are always already touching, already merged in shared circulation and intra-action. -107. Can we compost being? Is this action the only way to radically become-with? -106. Garbage trucks come on trash day, whether we are ready or not. There is no pause because the system depends on continuity. Systems anticipate breakdowns. Even failure has a protocol. -105. Something is humiliating about how much labor goes into preventing change. Hands sorting polymers by type. Hands washing surfaces that people will touch again tomorrow. Hands closing bags that will eventually open. -104. I notice how often people say “at least” when they talk about death as if comparison might soften the impact. As if suffering could be arranged on a scale and managed that way. As if ethics were a matter of relative outcomes. -103. Some things only make sense when they are stacked incorrectly. -102. The phrase “becoming-with” sounds generous until I remember how often becoming happens without choice. Without consent. Without reciprocity. Sometimes becoming-with is simply being unable to get away. -101. The tick does not ask permission. The tick waits. The tick senses heat. The tick does not care about your intentions, and often, we do not care about theirs. -100. My dad used to stack the hospital snacks: Lorna Doone™, Oreo™, Lorna Doone™. UNBLEACHED ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMINE MONONITRATE {VITAMIN B1}, RIBOFLAVIN {VITAMIN B2}, FOLIC ACID), SUGAR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, PALM OIL, CORN FLOUR, SALT, HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, BAKING SODA, SOY LECITHIN, CORNSTARCH, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR.[xi] UNBLEACHED ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMINE MONONITRATE {VITAMIN B1}, RIBOFLAVIN {VITAMIN B2}, FOLIC ACID), SUGAR, CANOLA OIL, COCOA {PROCESSED WITH ALKALI}, HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, BAKING SODA, SALT, SOY LECITHIN, CHOCOLATE, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR. CREAM DIP: SUGAR, CANOLA AND/OR PALM AND/OR PALM KERNEL OIL, ARTIFICIAL COLOR, SOY LECITHIN, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR. UNBLEACHED ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMINE MONONITRATE {VITAMIN B1}, RIBOFLAVIN {VITAMIN B2}, FOLIC ACID), SUGAR, CANOLA OIL, COCOA {PROCESSED WITH ALKALI}, HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, BAKING SODA, SALT, SOY LECITHIN, CHOCOLATE, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR.[xii] UNBLEACHED ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMINE MONONITRATE {VITAMIN B1}, RIBOFLAVIN {VITAMIN B2}, FOLIC ACID), SUGAR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, PALM OIL, CORN FLOUR, SALT, HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, BAKING SODA, SOY LECITHIN, CORNSTARCH, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR. -99. I am uneasy with the idea of “waste” as something that has failed. What if waste is simply matter that has outlived the world we built for them? Does matter know when someone discards matter? -98. A desire to interface with the more-than-human—to distill meaning down to a particle that can be digested and understood by every being. A way to send a message that you don’t need eyes to read. A message that passes through skin. A message that surpasses electrons’ inability to touch. A message that won’t repel off the veil. -97. “Here in the organic stratum, it seems obvious that Life responds to Problems by experimenting with different kinds of Solutions. Chaosmosis has always involved finding solutions to various problems: mountains, for example, are one solution to the problem of tectonic pressure; and diamonds are another. Due to differences in time-scale and speed, we may find it hard to identify with a rock’s struggle to survive (although it, too, is bound to die, in its own way), whereas the survival struggles of other mammals and even of plants often strike a chord in us.”[1] -96. a deep breath. a pause. -95. Eventually, surfaces tell on themselves. -94. Sometimes I catch myself performing complexity. I worry that even refusal can harden into form. I worry that opacity can become just another surface. -93. The archive renumbers. The landfill compacts. The Nurses chart. These are rhythms. They repeat whether I am paying attention or not. -92. They do not pretend to clean what they transform. They do not promise purity. -91. Ethics is not just about responsible actions in relation to human experiences of the world; rather, “it concerns material entanglements and how each intra-action influences the reconfiguration of these. It is about the ethical call that is embodied in the very process of worlding.”[xiv] -90. a deep breath. a pause. another deep breath. a longer pause. -89. I keep returning to when the algae jiggled in my hand. Actual evidence of an interspecies dialogue. Like tuning in to some psychic force that enlivens us to make alongside each other. Like an ambient hum that we can both tune into. Like co-creating alongside each other. -88. “The task is to make kin in lines of inventive connection as a practice of learning to live and die well with each other in a thick present.” [2] -87. Layers of time pressing down at once. Past, present, and anticipated futures compacted into a single sensation. -86. I want to resist the temptation to make that numbness meaningful. Sometimes it is just absence. Sometimes it is the body refusing to participate in attunement. -85. In the hospital, you need so many things to sustain life. Plastic tubing. Metal poles. Disposable fabrics. Adhesives. Fluids. Sounds. Nothing feels disposable in the moment, even though everything is designed to be replaced. -84. Not between living and dead. Not between body and environment. Not between object and meaning. -83. Sometimes the most difficult thing is not touching, not intervening, not extracting meaning. -82. Bodies learn contact before they learn caution. -81. As I walked, I thought of how I felt bad for the trees soaking up leachate, but I didn’t feel good about the thriving microorganisms under the sand. I was curious about the edges of my empathy. I wondered about the beings that thrive in this place at the expense of other beings. I wondered about the morality of that. I wondered about the ethics of that.[xiii] -80. So now that I’m writing after goodbye, What if I run out of things to say? -79. “I [give] myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love.”[3] -78. The kind of folding-in and folding-out that happens with landfills. -77. Layers of time pressing down at once. Past, present, and anticipated futures compacted into a single sensation. My chest tightens, not because anything is wrong now, but because too much is touching simultaneously. -76. I think about how often we say something is “taken care of” when what we mean is “moved out of sight.” Care is frequently spatial rather than ethical. We rearrange proximity and call it resolution. -75. “Partially obstructing.” “Circumferential.” “No bleeding present.” -74. The more I try to trace where something ends, the more I notice where it continues. In the soil. In the archive. In the air. In me. -73. I keep noticing how often preservation appears as dismemberment. To save something, we: separate from its context, strip attachments, stabilize against change, But what of things that need to rot to stay alive? -72. What if decay was not the opposite of care, but its condition? -71. There is a difference between being held and being compressed, but sometimes I can’t tell which one I want. Pressure can feel like safety when the alternative is dispersion. -70. “Findings: An infiltrative partially obstructing large mass was found at 25 cm. The mass was circumferential. No bleeding was present. This was biopsied with a cold forceps for histology.”[4] -69. “Landfills (…) may be understood as ‘massive generating practices’ that ‘link human actors, technological capabilities, atmospheres, and ecologies in new configurations of contamination.”[xv] -68. “November 10, Embarrassed and almost guilty because sometimes I feel that my mourning is merely a susceptibility to emotion. But all my life haven’t I been just that: moved?” [xvi] -Roland Barthes -67. “We require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all. That kind of material semiotics is always situated, someplace and not noplace, entangled and worldly. Alone, in our separate kinds of expertise and experience, we know both too much and too little, and so we succumb to despair or to hope, and neither is a sensible attitude.”[5] -66. Everything bleeds a little. -65. A new ecological poetics, based on the recovery of detritus. -64. The kind of green that sits exactly across from blood red. -63. Sometimes the most honest thing a system can do is leak. -62. The archive promises safety through order, but order is never neutral. To number is to decide what counts as one. To rehouse is to interrupt a relationship. To label is to replace a history with a category. I am interested in the moment when the archive fails—when smell escapes, when plastic sweats, when context insists on returning. -61. I keep returning to the idea that ethics might be a sensory practice. Not a rule, but an attunement. A willingness to notice what touches you back. -60. Compacted remnants of his journal; Green apples deep talk sent from not the best day popcorn for lunch chow it down how to play enjoy the easy girth and fried chicken Jell-O installing #9 with peppers down nobody else isn’t as good as real with me NOT in chaos dont have any fun M to be around this year eat in the bathrooms stalls capture it better master tinker first night of the year getting chemo party How is it that no one has rick rolled the harlem shake? twinkies chicken in a biskit a candy called Scentos. proud moment woooop woooop plain, frosted white, or frosted pink? round the outside full size please bring more still no sign There is always room Krispie treat you know where it came from unusually quiet today and I like it to help me cross between Fruit by the Foot might be one of the tastiest candies ever made -59. I’m interested in moments when containment fails—when what is meant to be preserved, numbered, and named seeps through prescribed borders. I am drawn to the slow leak of order, to the leachate that forms when materials, bodies, and beings meet in unwanted intimacy. These moments of seepage expose the impossibility of clean separation (or any separation) and the persistence of what we try to bury. -58. Every April he goes on hospice and every May he dies -57. “I compost my soul in this hot pile. The worms are not human; their undulating bodies ingest and reach, and their feces fertilize worlds. Their tentacles make string figures.”[6] -56. Everything leaks a little. -55. Labor is a form of denial practiced collectively. -54. A device that protrudes from the wall; everyone seems to know the purpose, but the use remains unclear to me. -53. I think about how “it’s contained” is a way to calm ourselves, as if containment were not an ongoing labor that always fails eventually. -52. Various metal contraptions that, for a moment, looked like what I was supposed to be looking at. -51. Compunctio (compunction): to be pierced emotionally or affectively. Something that pierces you (like a pinprick). -50. I remember peering into my grandfather’s casket and seeing that they chose to bury him with his prosthetic arm. -49. “Leachate defines a particular ‘cutting together-apart’ that produces known as well as unknowable biological forms, as the latter transform quickly into new forms.” [vii] -48. passing through like the green in leaves there, colors and souls taste like each other -47. “…in nonarrogant collaboration with all those in the middle. We are all lichens; so we can be scraped off the rocks by the Furies, who still erupt to avenge crimes against the earth.”[7] -46. -45. The leather-covered cushions attached to the metal base and the plastic wheels. -44. -43. I’m still not over what they did to David Wojnarowicz’s Magic Box (59 collected objects originally stored together in a pine fruit box he labeled “Magic Box”). The Archive Curator re-labeled “Series XIII: Objects and Artifacts, 1914-1992, inclusive; Subseries B: The Magic Box” and displaced the objects from their container. -42. I feared (and would run away from) the squeaking of swings, basketballs bouncing, fireworks, and large crowds. -41. Complex de-stratifications and re-stratifications, the endless potential intra-actions organized into defining waste as human, inhuman, disposable, reusable, risky, determinate, containable, profitable, inert, anthropogenic, and ethical. [ix] -40. I carried him up the stairs—Kinked polyvinyl chloride. -39. A unit of language followed by silence. -38. Entanglement happens when an object appears deeply connected to another, so that if one orients a certain way, the other will immediately (faster than light) adjust in a complementary way. The objects are separate but “the same”.[iv] -37. Time is not a clock. -36. -35. My sister learned to crawl in the hospital while my father recovered from surgery. -34. I mean heat. I mean the violence of decomposition. I mean the way identity loses its edges under microbial labor. I mean violent composting. I mean metabolic chaos organized just enough to generate fertility. -33. On Saturday, I passed by museum display cases emptied of prior artefacts, either awaiting the return of the objects or their replacement. The remnants of the previous exhibition’s lighting rested on the walls and floors of the display cases, illuminating what was left. -32. I can only feel this—the earth rumbling through me. Rocking restlessly, impossibly experiencing tectonics without a source. -31. Sometimes I think about how underneath the grass, the earth, the concrete box, the steel box, the foam cushion, rests… -30. There is an urge to make the landfill instructive. To turn it into a lesson about responsibility, about consequence, about systems thinking. But sometimes the landfill is just a place where things are put because no one knows what else to do with them. -29. I wanted to be one But not singular. -28. I was becoming something, not anything in particular, just becoming something. -27. Waiting is a mode of being-toward. -26. The cancer metastasized. -25. Caribbean Blue scrubs with endless pockets. -24. A leaking landfill that reveals what is underneath, “appearing is a not-showing-itself.” [v] -23. When one perceives and object as two (package/product, artefact/stand, display/case, specimen/dish), the space between the two fitting parts is particularly charged. When one presses their hand into that void, the distance hums, and the vibration is felt on the hand. The mass of each (perceived) part bends the 4-dimensional mesh; the hill becomes a valley, and the “two” objects experience a gravitational pull toward each other. -22. The sound beats through my whole being. Making me wonder if I have control over my edges. Or is “I” permeable? -21. He is always already dead, and always already alive. -20. The microbes do not care about our moral frameworks. They do not hesitate. They do not reflect. They metabolize. This is not purity; it is indifference structured by chemistry. -19. to be dearer to dirt -18. “With “mechanical confidence.” [In cat’s cradling, at least] two pairs of hands are needed, and in each successive step, one is “passive,” offering the result of its previous operation, a string entanglement, for the other to operate, only to become active again at the next step, when the other presents the new entanglement. But it can also be said that each time the “pas-sive” pair is the one that holds, and is held by the entanglement, only to “let it go” when the other one takes the relay.”[8] -17. Time is not clock-time. -16. -15. Plastiglomerate is evidence that “everything is ultimately enfolded back into the geologic layer, including plastic.” [9] -14. I am drawn to objects that still remember being held. The dent in a cushion. The bend in a metal handle. The way plastic yellows where hands once rested. These are records of contact that did not fully interrupt themselves. Touch leaves residue. -13. “From October 2020 through October 2021, objects in Series XIII were assessed and rehoused as part of the Kress Fellowship in Plastics Conservation. Plastic items were rehoused to group like polymers together in the same boxes and prevent further degradation. Benign plastics are housed in Tyvek or tissue with silicone-coated mylar. Cellulose nitrate and acetate are housed in boxes that allow for air circulation. PVC is stored in non-vented mylar bags to inhibit plasticizer degradation. Rubber and polyurethane are housed in oxygen-free environments with oxygen scavengers inside of bags. Non-plastic objects were also rehoused to consolidate boxes and provide better protection for items within each box. Boxes throughout this series were then renumbered seriatim.”[ii] -12. Affects transpierce the body like arrows I sliced my finger with the dull part of wood, I bleed with the sap seeping from the skin. The word made flesh—we are always-already one. I sliced my finger with a washed-up shard of glass I leech with the landfill that could not be capped. We are always-already one—we are co-ill. -11. The bones, the clothes, the goo, and a chemo port. -10. Their smallness made me slow to notice—only little rustles in my hair that caused an itch. And an itch that sent them cascading from the top of my head. And in my head, the panic of realizing something else could’ve been living inside me. -9. Sometimes I forget that you were ever alive. -8. Grief is a path to understanding entangled shared living and dying; human beings must grieve with, because we are in and of this fabric of undoing. Without sustained remembrance, we cannot learn to live with ghosts and so cannot think. Like the crows and with the crows, living and dead, “we are at stake in each other’s company.”[10] -7. Thinking with plastic/geological time. -6. An attempt to make a text that feels like a landfill. -5. “We use the term plastiglomerate to describe an indurated, multi-composite material made hard by agglutination of rock and molten plastic. This material is subdivided into an in situ type, in which plastic is adhered to rock outcrops, and a clastic type, in which combinations of basalt, coral, shells, and local woody debris are cemented with grains of sand in a plastic matrix.” [11] -4. Perhaps the interest is less in entanglement and more in encasement. It matters which containers contain, and it matters what is contained in containers. -3. I heard someone say Heidegger’s being was a brain with hands. But sometimes I feel more like a body without a brain or maybe that my body IS my brain—that my way of understanding the world never passes through this entity called “brain” and instead is felt on my skin and interpreted in my skin. -2. An empty oxygen tank, a running oxygen compressor, tubes, a nasal cannula, and a collapsible stretcher. -1. I heard the landfill described as an endpoint. Still, perhaps a more accurate analysis is that the landfill is a beginning that no one wants to claim—a site where materials enter new relations without narrative support. 0. Sometimes, I think you miss me too. 1. “Suffering, like a stone (around my neck, deep inside me).”[x] 2. 3. 4. “Here, we report the appearance of a new “stone” formed through intermingling of melted plastic, beach sediment, basaltic lava fragments, and organic debris from Kamilo Beach on the island of Hawaii. The material, herein referred to as “plastiglomerate,” is divided into in situ and clastic types that were distributed over all areas of the beach.[12]” 5. Sympoiesis: “collectively-producing systems that do not have self-defined spatial or temporal boundaries. Information and control are distributed among components. The systems are evo-lutionary and have the potential for surprising change.”[13] 6. A rectangular patch of topsoil (28 x 84 inches) rests on a grey-painted wooden floor. On the left and right edges of the soil surface, bent metal structures resembling simplified medical bed handles are present. Resting on the soil is an irregularly shaped sheet of transparent bioplastic. On the bioplastic is an oil painting of a hand with its index finger extended—pinching skin together. Layered over the image, mirrored text reads, “Can we die while we are held?” 7. A swing set that pulls the world out from underneath me. 8. Time compresses as I sit on the couch where his hospital bed used to be, saying hello where he said goodbye, looking out the same window at different trees, leaning up against the same wall painted a different color, breathing where he stopped breathing. 9. I want to write something that behaves like leachate—moving between registers, picking things up, altering compositions as they go. Something that cannot be cleanly cited or stabilized. Something that resists (and simultaneously encourages) being skimmed. 10. I’m scared I won’t see you anymore. 11. The ticks taught me the limits of my own desire for controlled kinship. I considered how I wanted to touch without being touched back by every being. To approach the more-than-human on my own terms. 12. “it matters what ideas we use to think other ideas (with).”[14] It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.[15] 13. Speaking digitally (what is being said rather than how or to what end) so that the message can be transcribed into text with little loss.[viii] 14. 15. HIPAA. 16. Three Oriented Strand Board boxes with three metal holders, and three landfill stones. 17. the claw clip in my hair bumping against the subway train like dying it’s important to stay alive the crooked part of my teeth with my tongue the pressure to produce cold air in my lungs fear that it’s from concrete in my lungs distant from my dad impatient as my train is delayed dirt under my nails like I’m running out of time like I’m dying like I’ll get cancer from stress close to my dad concrete dust on my hands the cold air on my face like I need to go to sleep uneasy pain from the cut on my finger my heart race afraid I’m not communicating clearly 18. Sometimes I feel the need to be compressed, like the energy is erupting out of my skin, and if touch doesn’t touch back, the energy will escape from my being. 19. Leachate: a heterogeneous mix of heavy metals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, phthalates, herbicides, pesticides, and various gases, including methane, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen sulfide.[iii] 20. Language may rot in the mouth. Messages may be intercepted by microbes, wind, or ticks. Contact may not be welcome or safe. To reach across any boundary may risk contamination. 21. Agency circulates across networks of beings and things.[16] Ticks are not symbols. They are agents. Their possible intrusion into my body was not metaphor but metabolism. 22. I did not want to become-with in that way. 23. 24. A transparent grey Home-Depot bucket with anthrospira platensis bubbling 25. 26. I’ve stopped saying “it.” Not because I am policing language for the sake of precision, but because I am increasingly uncomfortable with the flattening it performs. It slides into sentences easily, but something goes missing each time I use it. 27. My spine hunched under the weight of the sky pressing me down. 28. Globus Pharyngeus. 29. Remnants of plastic soles of shoes, sand, a block of blue Styrofoam, a stingray carcass, and a landfill stone. 30. R.S.G. 1972-2013. 31. The kind of entanglement I need is what is. But I only have access in the way symptoms present themselves. 32. 33. 34. I think about compression as a kind of care that is not gentle. The way trash is pressed into itself, forced into proximity with what they never intended to touch. Compression does not ask for consent; it produces a relation by force. Still, something is comforting in the idea that pressure might hold things together long enough for transformation to occur. That, without compression, everything would disperse too quickly to become anything else 35. 36. “Showing themselves as thus showing themselves, ‘indicates’ something which does not show itself… Thus appearance, as the appearance ‘of something’, does not mean showing itself; it means rather the announcing-itself by something which does not show itself, but which announces itself through something which does show itself… Appearing is a not-showing-itself…” [v 37. Two horse-rendering plants, fish oil factories, and garbage incinerators.] 38. I wonder if grief is a kind of leachate. Both form when pressure, time, and matter meet. Both carry traces of everything they pass through. Neither are clean nor contained, and neither are easily neutralized. Both move downward, laterally, and unpredictably. Neither disappears just because we cover them. 39. 40. Transported, compacted, and covered with sand from Jamaica Bay. 41. It matters which compost makes compostables. It matters which waste makes waste. It matters which leachate leaches. [1] Holland, Eugene W. Deleuze and Guattari's 'a Thousand Plateaus' : A Reader's Guide, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/newschool/detail.action?docID=1363754. [2] Harraway (keeping with the trouble 1) [3] Walt Whitman, Leaves of grass [4] Notes from my father’s first colonoscopy [5] 4 KWTT [6] 34-35KWWT Harraway [7] 56 KWWT [8] 14 (Isabelle Stengers in KWWT 34 [9] (10 Plastic Matter Heather Davis) [10] 25, 39KWTT [11] Colin N. Waters et al., “An Anthropogenic Marker Horizon in the Future Rock Record,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 5–6. [12] Colin N. Waters et al., “An Anthropogenic Marker Horizon in the Future Rock Record,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 1. [13] 33 KWWT M. Beth Dempster. Autopoietic and Sympoietic Systems [14] Marilyn Strathern The Gender of the Gift [15] Donna Harraway, Keeping with the Trouble, 12 [16] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).