That Which is Read by the Body

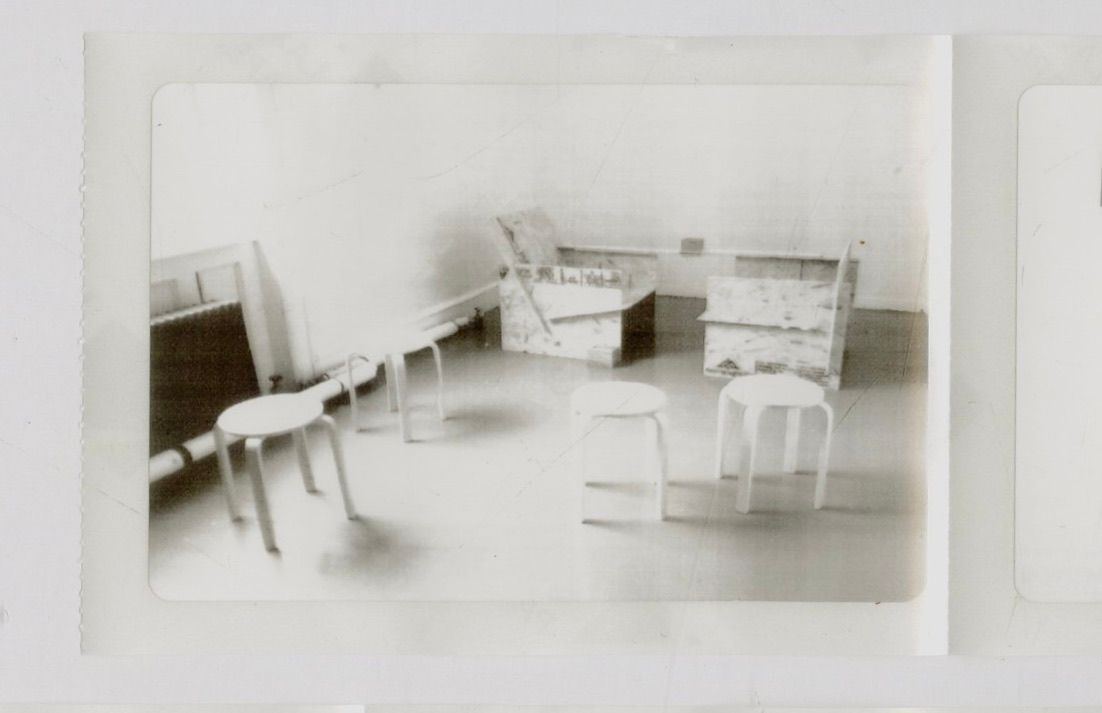

That Which is Read by the Body, 2025

NAF OSB, Canned Peaches, Food Coloring, Found Walnut, Tissue Paper

Parasites and Poetics: The Instability of Transmission

Several months ago, I wrote the following paragraph as a starting point for discussing my art practice. Reading these words back now, I am recognizing them more as an ironic prophecy. I wrote:

“I carry with me a desire to interface with the more-than-human—there must be some process that can distill meaning down to a particle that can be digested and understood by every being. A way to send a message that you don’t need eyes to read. A message that passes through skin. A message that surpasses electrons’ inability to touch. A message that won’t repel off the veil.

A message that you don’t need to be alive to read.”

As I dissect my own words, I am perplexed by these desires and the intricate ways in which they mirror the desires that other parasitic creatures had toward me in an experience I had this June.

Last month, I walked on the shores of a place I’m having trouble categorizing. In the 1850s, Dead Horse Bay (then called Barren Island) was the site of two horse-rendering plants, fish oil factories, and garbage incinerators. A community of European immigrants and formerly enslaved African Americans worked in these industrial plants and instituted their own governmental system, largely outside the municipal system.

A century later, Robert Moses destroyed thousands of low-income Brooklyn homes to make way for reform projects and highway networks he planned to construct throughout the city.1 Along with other waste from Manhattan, materials and belongings from these destroyed neighborhoods were transported to this site, compacted, and covered with sand from Jamaica Bay to extend the shoreline. A couple of years later, the landfill was capped (before plastic fully infiltrated community systems), but erosion has released much of that trash, which collects on the bay’s eastern shore.

This shoreline was simultaneously a waste-world and a place where life seemed to thrive. The sand was full of impacted waste from the pre-plastic city. There was an immense calm, and a tranquil sound that echoed when the waves crashed on the discarded, covered, and compacted glass. As I walked, I thought of how I felt bad for the trees soaking up leachate, but I didn’t feel good about the thriving microorganisms under the sand. I was curious about the edges of my empathy. I wondered about the beings that thrive in this place at the expense of other beings. I wondered about the morality of that. I wondered about the ethics of that.

When there, I picked up several “landfill stones” (they resemble giant rocks but are actually formed from compacted waste from the site, essentially the sedimentary rocks of the Anthropocene) and carted them back through the tall grasses that one needs to walk through to reach the bay.

On my return home, I encountered two ticks crawling around my scalp. I’m still not sure if they came from the “stones” or if they leapt from the grasses on my entrance or return.

A third tick revealed themself a week later.

Their smallness made me slow to notice—only little rustles in my hair that caused an itch. And an itch that sent them cascading from the top of my head. Then the panic of realizing something else could’ve been living inside me. I had spent years thinking about porous boundaries, longing to blur the line between myself and the more-than-human world. But this wasn’t metaphor. This could’ve been puncture. Skin breached. Intimacy turned involuntary.

And to think that only a month before, I had desired “a message that passes through skin.”

The ticks reminded me that touch isn’t innocent. In On Touching—The Inhuman That Therefore I Am, Karan Barad dismantles the idea of discrete entities bumping into each other.

Instead, touch is a condition of mutual becoming: we are changed by every contact. And the ticks made me think of touch as more sinister. They collapsed the safe conceptual space of “intra-action” into a more bodily reckoning with shared vulnerability. I did not want to be touched like that. I did not want to become-with in that way.

This experience has made me reconsider my relational aesthetics work, That Which is Read by the Body.

The first time I performed this project was also my first meeting with Gregg Bordowitz. I was interested in experiencing him experience the words. I invited him into my studio and asked,

“Do you have any allergies?”

Confused, but intrigued, he replied, “No?”

I then explained to him that I had made some poems from food-grade food coloring and canned peaches, and asked if he would be willing to participate in a performance with me.

He said yes.

Choosing to engage, he took a seat across from me.

On the table was a note that read:

That Which is Read by the Body is a participatory piece involving the placement and consumption of an edible message. Please read before engaging:

That Which is Read by the Body is a participatory piece involving the placement and consumption of an edible message.

For this work, I am writing an ongoing poem/letter with no beginning or end and can be read in any direction; some call and respond to each other, and some don’t yet have their companion. Like Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet, the poem relies on someone other than the author or reader to arrange the pages

This text generates meaning between the writer and the reader by matching two halves of a text. It is a meaning not accessible to others.” (Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet, An Essay (Princeton University Press, 2023), 99.) These letters can’t be passed by hand; the reader has no hands, eyes, or body… I need this message to be translated to a particle singular enough to be universal.

If touch isn’t touching (since electrons repel)(Karan Barad, On Touching), this message must involve the transfer of electrons. A message where both parts have a corresponding valence, a message that would so desire to cling to another that they become one. The means of sending this message would be a way of giving and receiving information that actually becomes part of the writer and reader (because this is the only way for them actually to touch).

Ingredients & Allergies: Made from food-grade food coloring, agar-agar, and canned peach and pear juice. Do not participate if you have allergies to these ingredients.

Hygiene: Please wash your hands before handling materials.

Consent & Comfort: Participation is voluntary. You are welcome to observe rather than take part.

I reached into a 4”x6” box and pulled out two small envelopes. I handed one to him and held the other in my hands. I told him that I would go first.

I opened the envelope, and inside was a small piece of paper with these words inscribed:

- Hold the note.

2. Place the words on your tongue.

3. Press. Briefly, and peel away.

4. Show your tongue.

5. Let another read.

6. Listen.

7. Eat the words.

8. Wait for words to dissolve.

Behind this paper was a 2-3 inch yellow-orange semi-transparent material with backward black text. When I placed the material on my tongue, the text transferred, and I stuck my tongue out. Gregg leaned in and read the words:

“I’m not sure

you’re there.”

Then I ate the preserved fruit.

Gregg then placed the words on his tongue.

I read:

“I hope.”

We smiled at each other awkwardly. This is a very weird thing to do with a stranger.